Q+A: Perspectives on Modeling and Drawing in Architecture

by Derek Noble, AIA, LEED AP

Architectural models—whether physical or digital—play a crucial role in communicating design concepts, making ideas accessible and comprehensible. Thoughtful model-making bridges the gap between abstract vision and tangible experience, allowing clients to immerse themselves in a proposed space and engage with the designer’s intent. By considering both analog and digital approaches, architects can enhance creativity, collaboration, and comprehension, ultimately shaping more innovative and effective design outcomes.

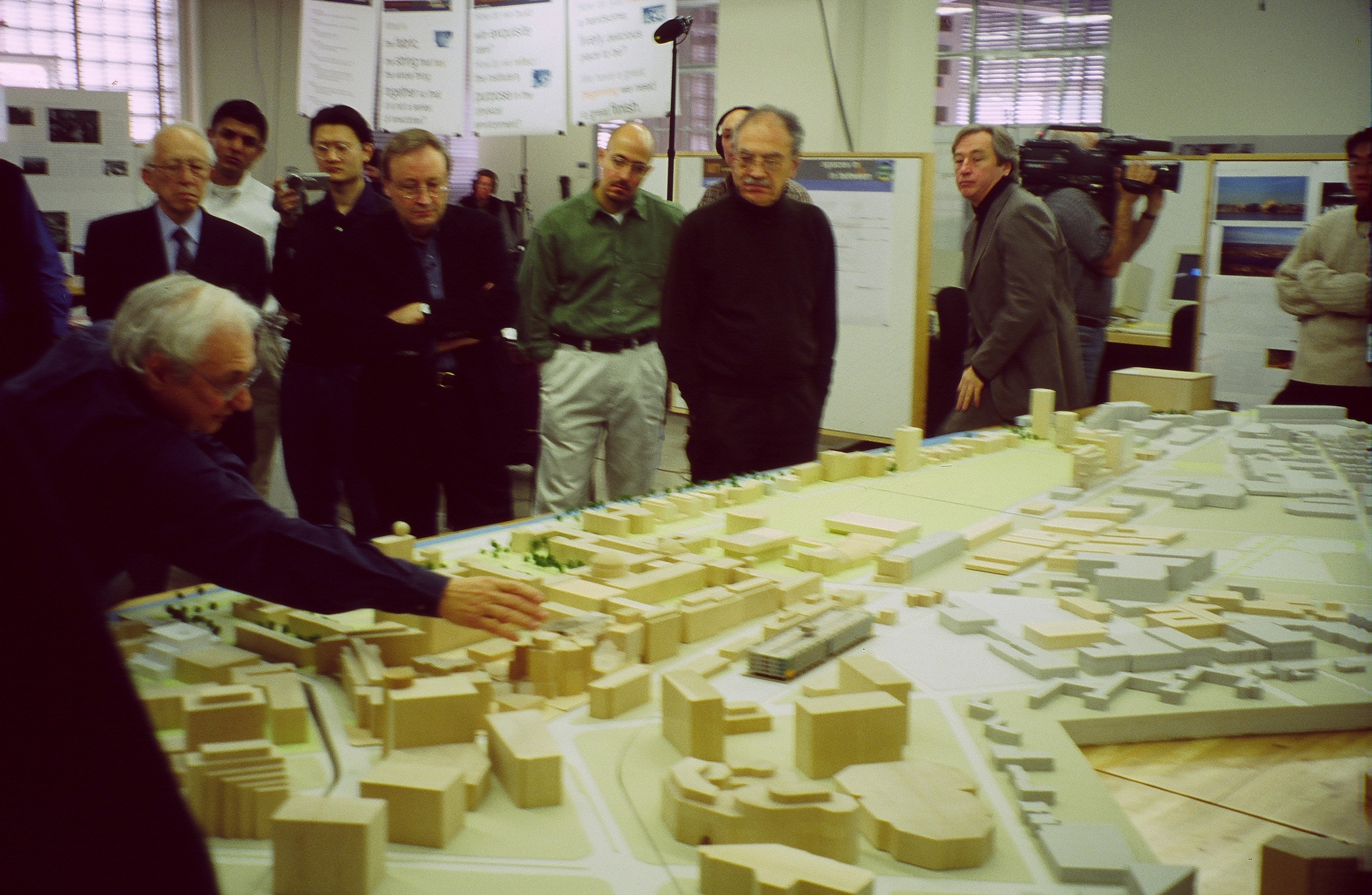

Architectural Model by Christian Moneyhun. Photo by Marjorie Becker/Accidentally Wes Anderson.

Derek Noble is an architect and Principal at Shepley Bulfinch, bringing decades of experience leading complex healthcare and academic projects. Known for collaborative leadership and client-focused design, he guides multidisciplinary teams to deliver thoughtful, high-performing environments that advance patient care, research, and education across diverse institutions nationwide with clarity and purpose.

Christian Moneyhun is an experienced architectural designer and model maker, known for his intuitive approach to physical modeling and hand drawing. With 36 years at Shepley Bulfinch, Christian values the tactile creativity of analog methods, while skillfully integrating big-picture thinking to communicate concepts and inspire clients.

Larry Sass is an MIT professor of architecture known for digital design, computational fabrication, and innovative housing systems. His work explores prefabrication, mass customization, and sustainable construction, bridging research and practice through teaching, publications, and built projects that rethink how homes are designed and produced using advanced technologies worldwide today. Larry is also a former Bulfinch and currently serving on the firm’s Board of Directors.

Derek Noble (DN): Let’s start with the basics. In your experience, what makes a good architectural model, whether it’s 2D or 3D? How do you see its role in communicating ideas to clients?

Christian Moneyhun (CM): A good model, in my view, needs to clearly relate the concept—it should be a clear message for the client, so they instantly understand what you’re trying to do. Most of my models are used for interviews, and I keep them simple and straightforward. Many clients aren’t trained in architecture, so the model should walk them through the concept as if they’re learning from scratch. It’s about making the initial idea accessible and understandable.

Larry Sass (LS): I agree. The model should convey the project’s concepts. But when you move from handcrafted analog models to digital ones, the possibilities expand. With digital models, you can extract drawings, create 3D prints, render interiors, and even animate—all from the same digital input. The goal is to enhance learning, exploration, and explanation in ways that handcrafted models cannot.

DN: How do you see the difference between physical and digital models in terms of client engagement and comprehension?

CM: Physical models, especially at a small scale, let people grasp everything at once. You see the buildings and the object of discussion in a tangible way. Digital renderings, on the other hand, immerse you in three dimensions—like showing my mother a rendering, she’d understand it instantly as if it were a photograph.

DN: That’s a great point. Whichever medium you use—digital or physical—it’s about capturing an idea and making it accessible. For many clients, this might be their first experience with the design process. The concepts that feel familiar and intuitive to us, as designers, can be completely new to them. These models are a chance for our clients to put themselves into the space and experience our vision.

LS: Absolutely, both mediums put the audience into the project in ways that two-dimensional drawings can’t. But it’s important to remember that CAD (computer aided design) software was originally invented to run machinery, not just to make drawings. The same CAD model can be used to fabricate building parts, just as it’s done in car manufacturing and furniture design. In architecture, though, the industry often pulls back from this potential.

Frank Gehry’s studio. Photos by Larry Sass.

DN: Larry, you’ve worked closely with Frank Gehry’s studio. How did Gehry’s approach to modeling influence your perspective?

LS: Frank Gehry’s process is fascinating. He starts with paper models, then scans them and manipulates them digitally in programs like Rhino. I taught a class with the head of Gehry Technologies and I asked why Frank doesn’t go straight to the computer. The answer: he loves working with his hands. There’s a tactile, intuitive reaction he gets from paper and metal that digital tools can’t replicate.

CM: That resonates with me. There’s something about the resistance of pencil on paper, or the feel of cardboard, that’s deeply intuitive. I love SketchUp for its ease, but for curves and arcs, I still prefer trace paper and physical tools. The process is more fluid and inspiring when working by hand.

Alfred R. Goldstein Library, Ringling College of Art and Design, Sarasota, FL.

DN: Is there a creative gap between digital and analog methods? How do you balance the two in your workflow?

LS: When you use a computer, you’re making symbols. Operations require deliberate steps, whereas drawing by hand is fluid and spontaneous. The computer is great once you know what you want to do, but for problem-setting and ideation, handcrafting is still superior. It’s about fluidity versus symbolic thinking.

CM: I agree. My process is a combination of hand sketching and digitizing, but there’s an excitement and sense of discovery I get from pen and paper that I just don’t feel when I’m on a computer. And every designer is different; one of my friends worked in Frank Gehry’s studio. He can’t sketch at all but give him Rhino and he comes up with the most amazing models I’ve ever seen.

DN: That’s true. When I think about my personal process—hand sketches, then digital modification, then back to hand for changes—it’s never just one or the other. The computer speeds things up, but the flexibility and intuition of hand drawing remain essential.

How do you see the future of modeling in architecture, especially with influences from engineering and other industries?

LS: Architecture often adopts standards from engineering but rarely sets them. Most buildings are prototypes, and the industry changes slowly. It’s amazing how we’ve adopted building information modeling in the last 25 years. Digital modeling has transformed workflows and allowed for new levels of precise collaboration throughout the design process, but there’s little incentive to change further unless there’s a clear cost benefit.

CM: I feel like societal expectations and strict codes, especially in the U.S., make innovation challenging. For example, if you go to a hardware store, it’s already engineering to fit a certain way: you have two-by-fours or two-by-tens, if you’re building out of wood it needs to be 16 inches on-center so a four-by-eight sheet can fit. Heaven forbid you want something curved!

Other countries with more flexible codes produce remarkable architecture. I can absolutely see both sides of it, but it’s about finding a balance between efficiency and creativity and educating engineers to collaborate with architects for more innovative solutions.

DN: I think integrated project delivery (IPD) is one approach that aligns with what both of you are saying. With all parties working from the same model, reducing liability and encouraging collaboration, like our current project, Penn Medicine Princeton Cancer Center.

Penn Medicine Princeton Health Cancer Center, Plainsboro, NJ. Rending © Shepley Bulfinch.

This has been a great discussion. The intersection of digital and analog modeling is a dynamic space in our industry shaped by tradition, technology, and creativity. Thank you both for sharing your insights.

*References: All content is drawn from a transcript of a discussion held on December 15, 2025.

Derek Noble, AIA, LEED AP

Principal, VP of Marketing + BD

As a principal at Shepley Bulfinch, Derek’s expertise ranges from complex renovation projects to new construction with challenging programmatic requirements across the education and healthcare design sectors.